- What is the process for the UK to leave the EU?

The only formal process to leave the EU comes through Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU). The government of the withdrawing state notifies the European Council of its wish to leave. This triggers the negotiation process around the transitional arrangement and also any future arrangement between the EU and the leaving state. Two years is allotted for the negotiations, during which all EU laws continue to apply to the leaving state. If no agreement is reached after two years, all EU rules and rights cease to apply to the withdrawing country – unless the period is extended by unanimous agreement of the other 27 states. The leaving country is not part of any discussions around the agreement and is essentially presented with a take-it-or-leave-it offer at the end of the negotiations. Any trade deal must also be approved by the European Parliament. The deal can be approved by qualified majority vote, unless it is seen to be a 'mixed agreement' which means it would need to be approved by all member states.

There is an open question as to when exactly Article 50 will be triggered. There is no legal obligation to trigger it immediately. Prime Minister David Cameron has made it clear that it will be up to his successor to trigger it and has targeted having a new PM in place by October. Delaying the triggering of Article 50 makes sense – the UK needs a plan, negotiating strategy and to decide exactly what it wants from the EU. Some informal talks with the EU may begin before it is triggered. However, there is little incentive and no obligation for the rest of the EU to begin negotiations on leaving until Article 50 has been triggered – ultimately the ticking clock seems to give them a slight upper hand in the negotiations.

- A transitional arrangement?

The first step will be to negotiate a transitional arrangement between the UK and the EU. This is essentially the holding pattern while the next steps take place. This would likely cover issues such as the rights of EU and UK citizens living abroad. It could well also involve a debate about the time period for negotiating the bigger UK-EU trade deal and whether the two years can be extended before negotiations begin. In reality though, this is likely to happen largely simultaneously with the negotiations for what comes next and what the new trading agreement with the EU is. It makes little sense to negotiate a transition without what you are transitioning to being relatively clear.

- What are the alternative options for the UK-EU relationship?

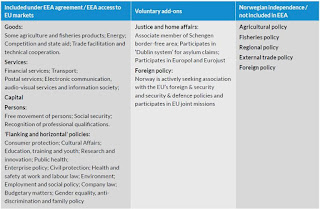

There are a number of different options, though none have been settled upon by the Leave camp, so one cannot conclusively say which might be chosen. The table below compares the options based on four tests – level of EU market access, say over the rules, gains in independence and negotiability. The challenge is striking a balance between market access, sovereignty/voting rights and control over immigration.

- Existing options

Norway/EEA: While this model scores highly in terms of maintaining market access, it falls short in terms of guaranteeing the UK a say over the rules (Norway has no veto at the European Council, no votes in the Council of Ministers and no representation in the European Parliament) and also in terms of independence, given that most EU policy areas would continue to apply post-Brexit – crucially including free movement of people. On the other hand, the UK would gain the ability to negotiate its own trade deals.

Switzerland/FTA: This model scores a medium in terms of continued market access – it is relatively comprehensive in terms of goods but falls short in terms of services access, particularly for financial services. It also fares poorly in terms of having a say over the rules with Switzerland essentially having to mirror EU legislation in key areas where it wants to secure single market access. It does score more highly than the EEA option in terms of gains in independence with several policy areas including social and employment law returning into the remit of the UK government.

Clean break/WTO: This model understandably scores low in terms of continued EU market access as it entails no preferential agreement with the EU. Some key goods exports would face high tariffs and accessing EU services markets would become much harder, particularly in financial services. Likewise it offers the UK no say over the rules but offers maximum scope for gains in independence and would not involve as complex negotiations with the EU.

- What about something new – aka 'The British option'?

Comprehensive UK-EU FTA (based on the Canada-EU agreement): This would be a comprehensive living agreement – meaning some level of permanent arbitration and engagement between both sides on things such as product standards and regulation. The Canada agreement offers fairly comprehensive access in terms of goods with 100% of tariff lines on industrial and fisheries products scrapped – nearly all of them upon entry into force, and the rest after transition periods of up to seven years. As regards agricultural products, the EU and Canada will eliminate 93.8% and 91.7% of tariff lines respectively, though some products will be exempt. Services access is limited, with a sizeable number of carve-outs from the deal secured on both sides. The agreement does not include any EU budget contribution or accepting free movement of people.

Unilateral free trade: Here the UK would drop tariffs on everyone unilaterally, avoiding the need for any free trade negotiations.

- How long might the exit process take?

As shown above the process involves a number of parts – negotiating a transitional arrangement, negotiating a new arrangement with the EU and negotiating to retain existing trade agreements with other countries and possibly sign new ones. This entire process could take some time and seems likely to take longer than two years. Evidence suggests that negotiating a free trade deal usually takes anywhere between four and ten years. This holds for both negotiations with the EU and those between other states.

However, there is evidence of a trade-off between speed and scope – the more comprehensive an agreement, the longer it takes to negotiate. The table below highlights that, while the relationship is not perfect, generally the more comprehensive trade deals – which include liberalisation or mutual recognition of services, investment, public procurement, intellectual property and qualifications as well as tackling non-tariff barriers more widely – tend to take longer to negotiate. The more basic agreements, which tend to involve just negotiating tariff reductions, tend to be relatively quicker and easier to negotiate.

One important point to keep in mind is that the UK-EU negotiation will be slightly different. It will not be about trying to bring together two different systems, since the two systems are currently the same. It will be more about working out what the UK or EU might want to change and then how the two move forward and interact in the future. This essentially amounts to starting a number of steps into the process, potentially making it slightly quicker and easier.

Source: Open Europe Analysis

Note: The above write-up is just for our understanding.

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "LONGTERMINVESTORSRESEARCH" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to longterminvestorsresearch+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

Visit this group at https://groups.google.com/group/longterminvestorsresearch.

For more options, visit https://groups.google.com/d/optout.

No comments:

Post a Comment